Where Does the Time Go?

The Epidemic of Dyschronicity and the Meaning of Time (Featuring: Nietzche! Heidegger! Lewis Mumford! And some various thoughts on some Greek and German words!)

How are you? I’m asked.

And I usually say something like, I’m good! Really good actually! Just can’t believe it’s already (insert month)!

It’s true. In many ways, I’ve never been better—and yet I feel a bit untethered, as if I can’t quite get a grasp on time or space. It’s like I’m on an automated conveyor belt—a quickly moving walkway in some interminable airport terminal. There’s no sense of day or night, only the incessant forward motion, my baggage gliding alongside me, faster still if I walk. Not in the sense that I am detached, disengaged, or disconnected (the opposite in fact!) but rather no matter how much I try and slow down—to savor, to enjoy, to “clock it”—time keeps accelerating.

Like so many others, I’m caught in a web of dyschronicity—not an actual acceleration of time, but the feeling that time is slipping away faster than it once did. Life is fleeting and ephemeral, and we are radically transient. The present feels reduced to a fleeting blip, a blink-and-you-miss-it moment, barely existing before it’s gone. Time isn’t just moving; it’s quickening, collapsing the present into a thin sliver that can’t hold its own weight. It hurtles forward, unstoppable, like an avalanche with nothing solid to grab onto.

I can hear the echoes of some elders, “Golly, time sure is flying!” And goddammit I get it now. And, as the ol’ adage goes, it’s as if the happier I am, the faster it goes. For me, this sense of “happy” seems directly linked to being busy. It’s not so much that every day is filled with good, but that it’s merely filled—and that, for better or worse, has been a surprising satisfaction. But with that busyness I’ve lost the capacity to linger, to dawdle, dally, or dither. To let time pass dissipate and come back together again. Time used to feel oceanic, with each drop gathering into something vast and immeasurable and meaningful. Now time is atomized—fragmented, reduced to vapors, slipping past before I can catch my breath.

We modern folks are scared of time passing (aka dying) and so I too have felt the pull of a common contemporary ideal—the belief that if I live twice as fast, I can squeeze in twice as many experiences, essentially living two lives in the span of one. If I could move infinitely fast, I’d theoretically approach the boundless horizon of the world’s possibilities, realizing a kaleidoscope of life paths in one single, brief lifetime! Wow! I cracked it! And with that, maybe I wouldn’t fear time passing (or death, the ultimate annihilator of options) so much! After all, if I’ve exhausted the possibilities, what would there be left to lose?

I know this is dumb.

A fulfilled life cannot be explained quantitatively. A long list of events—no matter how lovely and wonderful and good and novel—does not produce the tension which characterizes a meaningful story, while a very short story may nevertheless possess a meaningful tension.

What is Time?

Time is the rawest material of our life. The Oxford Dictionary defines “Time” as “the indefinite continued progress of existence.”

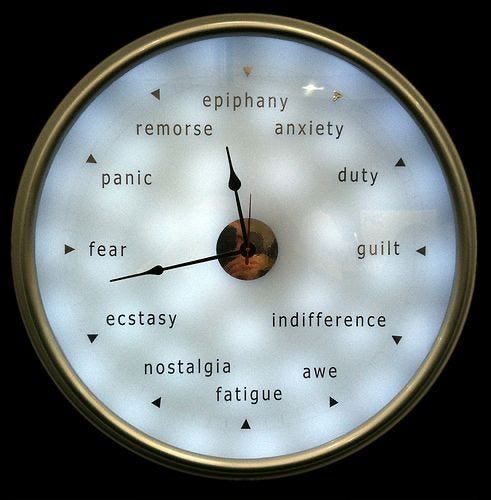

The ancient Greeks had two very different words for time.

One is Kronos: the time that we feel in our bodies and in our lives—the one we’ve have tried to organize our world around. That is the time of clocks and calendars. It helps us measure, plan, schedule and move forward.

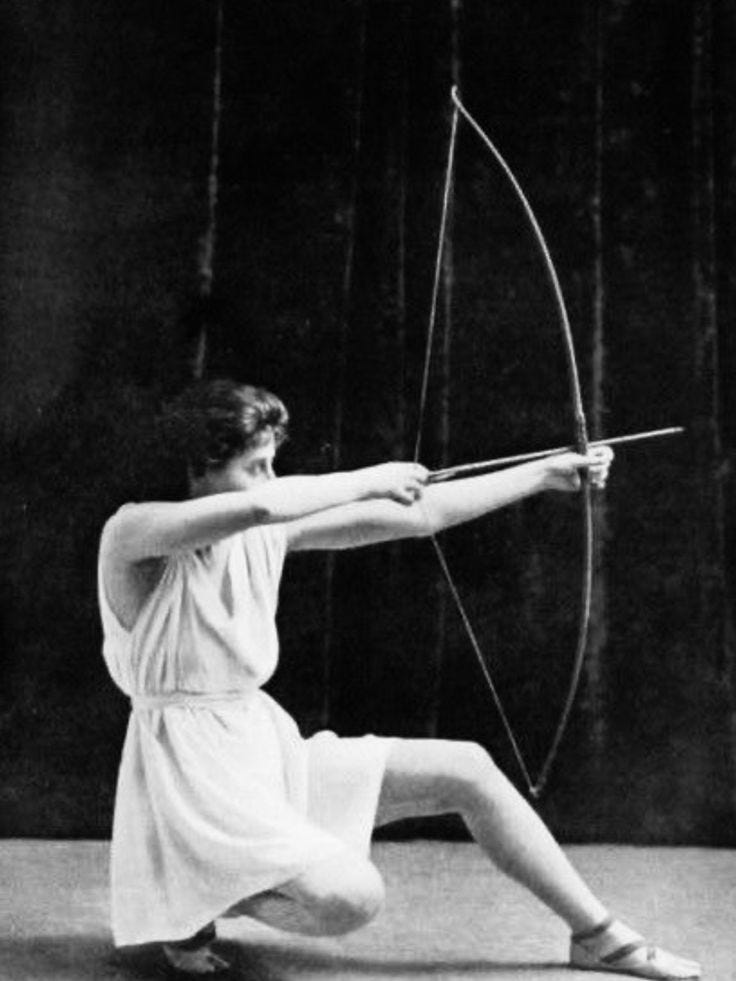

Then there is Kairos. This is an inbreaking—a moment that disrupts everything that came before, everything you thought you knew. It’s the harvest. The sound of opportunity knocking. It can be a sentence uttered by someone you love(d), the ringing of a telephone, and the witnessing of something that will change everything. Kairos moments are pivotal points. Life is suddenly, unalterably defined, separated into a Before ____ and an After_____. Kairos can be a millisecond, a season, or a century. Kairos originated in Greek archery, representing the moment when an archer finds the perfect opening to shoot their arrow.

There is a clear difference between these two types of time, but both times are very real. One is based on the ticking of the clock, the marking of the days of a calendar, the ringing in the new year. The other is based on opportunities or seasons. Is this the right time for me to make that jump? Is this time with my family and friends well spent?

What time is it? It might be noon in Chronos time, but in Kairos time, it might be the perfect moment for you to tell him you love him.

Each day we have the opportunity to wake up and either live according to our schedule, our to-dos, our calendars, or we can live according to our experiencing time in its multifaceted indefiniteness. Faced with this choice, we must ask ourselves: Are we living by the rhythm of our own internal narrative, or something external (and oddly equally as conceptual)?

Who’s To Blame?

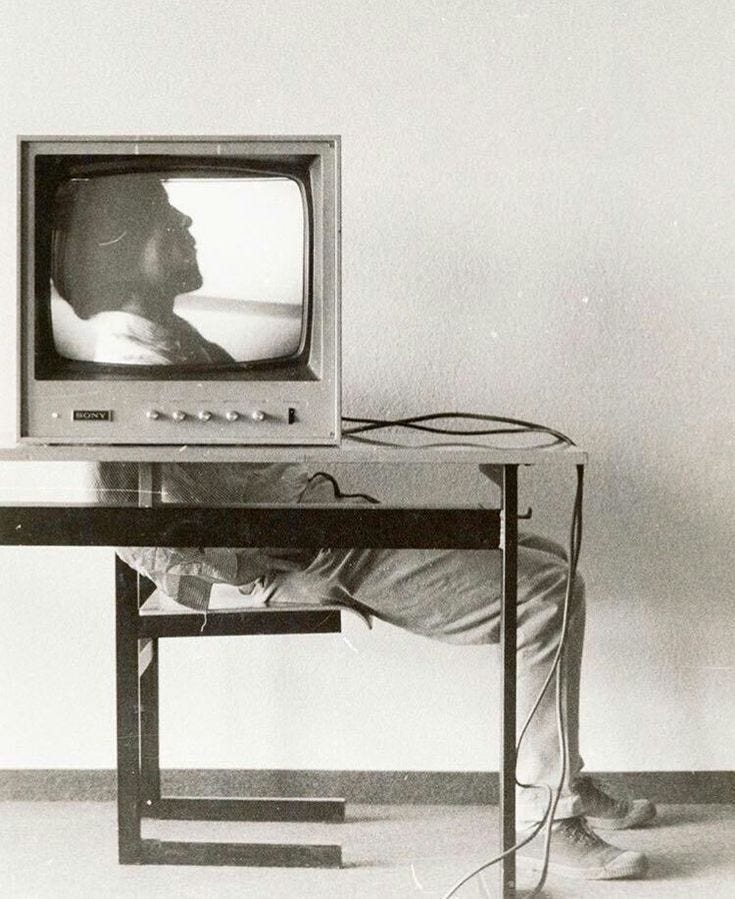

Historian and sociologist, Lewis Mumford, wrote in his 1934 classic, Technics and Civilization, that “the clock, not the steam-engine, is the key machine of the modern industrial age.” Due to the mechanical clock, “time-keeping passed into time-serving and time-accounting and time-rationing.” Mumford explains that, “as this took place, Eternity ceased gradually to serve as the measure and focus of human actions.” Humanity’s relationship to time was forever changed as “abstract time became the new medium of existence. Organic functions themselves were regulated by it: one ate, not upon feeling hungry, but when prompted by the clock: one slept, not when one was tired, but when the clock sanctioned it.” Keep in mind this was before phones, televisions, or the internet and yet he was putting his finger on something important: the shift from a natural, narrative, and organic view of time to a mechanized, segmented, and abstract view of time.

So, are machines to blame for the acceleration—and decay—of time?

Nietzsche, unsurprisingly, blamed our killing of God—our stabilizer of time who ensures a lasting perennial present. God’s death punctuated time itself and deprives time of any true tension. For Nietzsche, time requires an aim to be made meaningful and so he attempted to restore temporal tension via amor fati—a love of one’s fate. Amor fati is often associated with what he called "eternal recurrence", the idea that everything recurs infinitely over an infinite period of time—that one wants nothing to be different, not forward, not backward, not in all eternity. “Not merely bear what is necessary…but love it.” Basically, we can learn to experience time more meaningfully if we learn to love whatever fills it.

"My formula for greatness in a human being is amor fati: that one wants nothing to be different, not forward, not backward, not in all eternity. Not merely bear what is necessary, still less conceal it - but love it.".

-Friedrich Nietzsche

This embrace of amor fati offers a radical reframing of time: it challenges us to see every fleeting moment as inherently valuable, not because it leads to some grand culmination, but because it simply is. In a world stripped of divine scaffolding, Nietzsche’s vision dares us to find meaning not in transcendent eternity, but in the immanence of the now. To love one’s fate is to relinquish the need for linear progress or cosmic guarantees and instead root oneself in the cyclical, the repetitive, and the mundane. It’s not about passivity or resignation but about cultivating a deep, active affirmation of life, even in its smallest, most ordinary fragments. Through this lens, time (and death for that matter) no longer becomes something to overcome or conquer—it becomes something to savor.

Heidegger conveniently gave us Being and Time (gotta love a clear title)—and for him, time finds its meaning in death. That is, time is understood only from a finite or mortal vantage. Dasein's (his word for existence) fundamental characteristic and mode of "being-in-the-world" is temporal: Having been "thrown" into a world implies a "pastness" in its being. The present is the moment which makes past and future intelligible. Dasein is "stretched along" temporally between birth and death and thrown into its world; into its future possibilities which Dasein must take on.

Further, he connects the decay of time with the rise of mass society and increasing uniformity. Authenticity is an obstacle to society running smoothly and so with the acceleration of life it prevents the emergence of anyone who may deviate from the norm. His cure? Heritage. Tradition. “Authentic existence presupposes the handing down of a heritage.” Tradition and heritage create historical continuity via meaning making.

In other words? With the rapid succession of the new, Heidegger invokes the old.

Heidegger attempted to restore history in the face of its imminent end—and to, actually, restore it as an empty form—as a history that simply asserts its ability to form devoid of any real content. For Heidegger, experiencing history is enough to slow the decay of time—seeing our authentic selves in light of greater context and seeing time as something of great value . . . not just a commodity.

Heidegger draws a critical distinction between Erlebnis and Erfahrung—both of which translate to "experience." Erlebnis pertains to the outer world, encompassing events that happen to or around an individual. Heidegger critiques Erlebnis for its subjectivity, as it reinforces the separation between subject and object, reducing experience to fleeting, surface-level occurrences.

In contrast, Heidegger values Erfahrung for its connection to the “voice of Being.” Erfahrung delves into the inner world, emphasizing not just what happens, but what one makes of it. It is an experience enriched by reflection, imbued with meaning, and connected to one’s existence in a deeper, ontological sense. In a nutshell, Erfahrung emphasizes that you've learned something from your experience.

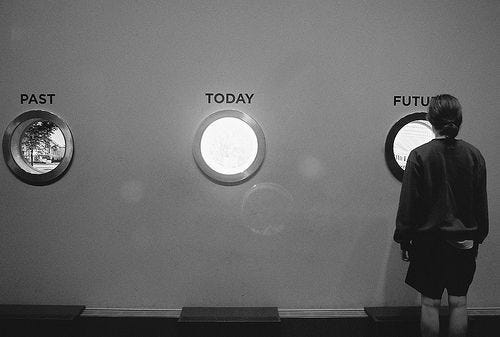

Where Erlebnis is point-like and impoverished in time, Erfahrung is expansive and time-rich. It allows the present to be viewed in the context of one’s past—heritage, history, education and accumulated experiences—making room for contemplation and growth. Through Erfahrung, time is not merely something to be spent; it is something that gathers, accumulates, and connects. The past, present, and future align in a meaningful continuum. Without this reflective engagement, one risks becoming a mere laborer of time, toiling through it without transformation, consuming things off without metabolization, checking things off just to tick a box—unlike the individual shaped and deepened by the vastness of Erfahrung.

"The most thought-provoking thing in our thought-provoking time is that we are still not thinking."

-Martin Heidegger

If I strip things of memory, recollection, or meaning, they become nothing more than a laundry list, a paper receipt, some random sheet from an expired calendar. It’s easy to think that acceleration is the intuitive answer to the problem of limited time or the disconnect between the world’s endless demands and my our fleeting lifespans. In a culture that prizes secular achievement and novelty, the pursuit of maximal enjoyment and the relentless optimization of one’s abilities have become synonymous with a life well-lived.

Time, at its essence, is both infinite and fleeting—a paradox we can neither solve nor escape. But perhaps that’s the point. The acceleration we feel, the dyschronicity that leaves us untethered, isn’t something to conquer but to inhabit differently. Maybe the task isn’t to slow time but to stretch its significance, to let each moment bloom and expand and swell. We can learn from Nietzsche’s amor fati to love what fills our time, from Heidegger’s Erfahrung to see our moments as part of a larger continuum, and from Mumford’s challenging of the mechanized rhythms that govern our day to day. Time’s fluidity demands that we engage it on its own terms, whether through the unrepeatable rupture of a Kairos moment or the slow, deliberate layering of meaning over Kronos.

To feel and experience time might just mean allowing ourselves to be caught up in its heartbreaking flow—forgetting altogether that it’s passing at all.

"Time is not something that passes by us, but something in which we exist."

-Martin Heidegger

This piece deeply resonates with me, especially the insight: "Maybe the task isn't to slow time but to stretch its significance, to let each moment bloom and expand and swell."

After years on the relentless 24/7 treadmill of living in New York and Los Angeles—constantly striving for more yet never feeling fulfilled—I made a life-altering decision recently and moved to Mexico, where time seems to flow more gently, allowing me to truly hear my thoughts and heart.

Here, I'm embracing Kairos time—the qualitative, opportune moments that invite deeper connection and meaning. And perhaps, it's the "perfect moment for me to tell him I love him"

Thank you for this great article. So many thoughts...but here are two: 1) Have you read Byung-Chul Han's "Scent of Time"? It intersects with your conversation perfectly. 2) The idea of time "accumulating" is so rich. It seems resonant with Merleau-Ponty's "thick" temporality.