On Noticing & Solitude

What Travel, Sarton, Sartre, and Descartres Reminded Me About Paying Attention

“Begin here. It is raining. I look out on the maple, where a few leaves have turned yellow, and listen to Punch, the parrot, talking to himself and to the rain ticking gently against the windows. I am here alone for the first time in weeks, to take up my “real” life again at last. That is what is strange—that friends, even passionate love, are not my real life unless there is time alone in which to explore and to discover what is happening or has happened. Without the interruptions, nourishing and maddening, this life would become arid. Yet I taste it fully only when I am alone here and “the house and I resume old conversations.”

- May Sarton, Journal of a Solitude

I spent the last month in a companied, social glow where newest and oldest friends wove in and out of my time traveling around Europe. Days on the Aegean as twelve of us traversed around via boat laughing, swimming, and eating three meals a day around a long dinner table. A visit to Portugal to see a beloved friend I’ve known since I was twelve—where we crawled up Lisbon’s steep, serpentine alleyways, drank vinho verde, and ate our weight in olives and sardines. A trip to Mallorca with my dearest friend from college where we rented a car and drove to a new beach everyday laughing and blasting ABBA to stay awake as we made our way back to the hotel far too late after losing track of the time given the long summer sunsets. We went on to Italy where a heat wave led us to spend lengthy chats over Aperol Spritzes between meandering walks in Rome and Tuscany.

Unusually, there were only three days in the last month that I was alone. Three whole days in Athens where the dust—but what felt more like glitter, sand, gold flakes—settled and I could see more clearly. In Athens I began to notice things in a way I did not during the rest of my travels. I remember a distinct moment on my first night as I walked home from the Odeon of Herodes Atticus (to see the London Philharmonic get drowned out by cicadas) when my solitary body cast a long, towering shadow across the hill of the Acropolis. In a place where I should feel small—insignificant even!—amongst the cosmos, the gods, the ancient ruins, I managed to feel larger than life. Wildly connected. Not only significant but essential. Oddly (at least for me) this is often the perspective that comes with solitude.

In Athens I would wake up and spend the day alone walking—without input, without negotiation, without plans. When there is no conversation you are able to converse with your self. When there is nothing you notice everything. When you’re not reminiscing you are able to taste the olive currently in your mouth. When you aren’t discussing what’s next you are able to smile at the old man picking at the bouzouki on the weathered marble steps. When there is no itinerary you can go back to the hotel for a bath, a bowl of pistachios, and a siesta and then rise from your nap to feverishly jot down every little thought and thing that struck you.

Eventually, I left Athens—and my solitude—and continued my Euro-jaunt, eventually finding myself leaning on an old windmill in Palma de Mallorca. I had gotten up a bit earlier than my friend and decided to walk down the street to get some coffee and finally do some writing. I hadn’t had a chance to since Athens (and being a happily routineless person, this is the only thing that makes me feel ~off~ if I don’t maintain). I was in Mallorca, one of the most beautiful places I’d ever been and was having the goddam time of my life—I was profoundly happy—but simultaneously…frustrated?! I was having trouble noticing, having trouble letting the scenes sink into that deeper more impactful place, and now, as I sat having a moment to myself, I was having trouble writing anything at all. No bubbling descriptions.

How could it be that I was experiencing so much beauty, newness, memory, joy, and yet had nothing to report?!

So, I made a list instead:

HOW TO NOTICE:

Deprive yourself of beauty so that the beauty stands out more. No! This cannot be true or correct. You must see as much beauty as possible in your lifetime without turning beauty into some comparative, qualified, or hierarchal thing.

In a pinch, isolate your senses. Only look! Only listen! Only taste!

Be rested…or exhausted completely. Either will do.

Be specific. Name the thing. Don’t just say “in the mountains” say in Serra de Tramuntana—on the trail between Cala de Deià and Deià itself in that place where the steps turned to rigid rock and when you look due East you see the perfectly manicured orange grove. Don’t just think “café” say that café in the old windmill in Santa Calina off Carrer de la Industra. But don’t always give it a name. Secrets help specificity blossom into individualized memory.

Do not be bound by time—others’, conceptual, or otherwise.

Be grateful.

Be undistracted.

Be alone.

In A Happy Death, Albert Camus said, “It takes time to live. Like any work of art, life needs to be thought about.”

The existential theme of the novel is the "will to happiness", the conscious creation of one's happiness, and the need of time (and freedom) to do so. To treat your life like a work of art is to notice. To notice is to “think about.” To think about means to have time, space, freedom, and solitude. I was happy and yet felt these missing pieces. It was as if the moment I made the list—a moment that inherently provided me the time/space/freedom/solitude I needed—I began to notice things in that spectacular, magical thinking way where connections, absurdity, depth, and beauty feel more apparent. That list became a prologue to my noticing.

Similarly, the protagonist of Sartre’s Nausea, Antoine Roquentin, becomes obsessed by his ability to notice—in this case a chestnut tree in front of him. He begins to reflect and focus on its bark and then its roots. He is struck by the “absurdity” of the roots, how they are absurd in relation to everything, even in relation to other parts of the tree. Even the affirmation “This is a root” begins to feel absurd.

“This root, with all its color, shape, its congealed movement, was . . . below all explanation. Each of its qualities escaped it a little, flowed out of it, half solidified, almost became a thing; each one was In the way in the root and the whole stump now gave me the impression of unwinding itself a little, denying its existence to lose itself in a frenzied excess.”

It's similar to Descartes’s experiment with wax, when he observes a sheet of wax, first considering all the sensible properties of wax—its shape, texture, size, color, and smell. He then points out that all these properties change as the wax is moved closer to a fire. The only properties that necessarily remain are extension, changeability and movability.

Whether its wax or roots or a windmill, if you look at things long enough you begin to notice which often means to notice things in its direct relation to you. You start to identify with the wax, the root, a structure, an olive and suddenly, absurdity is made personal:

“The essential thing is contingency. I mean that one cannot define existence as necessity. To exist is simply to be there; those who exist let themselves be encountered. . . .”

“Existence everywhere, infinitely, in excess, for ever and everywhere; existence—which is limited only by existence. I sank down on the bench, stupefied, stunned by this profusion of beings without origin: everywhere blossomings, hatchings out, my ears buzzed with existence, my very flesh throbbed and opened, abandoned itself to the universal burgeoning.”

Noticing—I mean reeeeally noticing—is often a matter of seeing beyond the surface, of making connections, and of seeing what is not there as much as what is there. It takes sustained effort and gathers up a heckofalotta cognitive function.

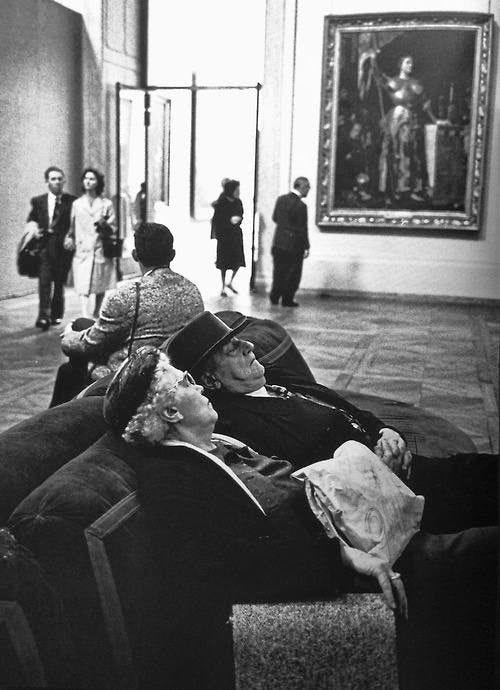

You’ve likely been to a museum and have experienced what’s called museum fatigue—a state of physical or mental fatigue caused by the experience of exhibits or museums first described in 1916. The possible reasons for museum fatigue are long: just plain exhaustion, satiation ("a decrease in attention [usually viewing time or percentage of stops to view] after repeated exposure to, or consumption of things that start to feel similar, stress, information overload, object competition ("a decrease in attention resulting from the simultaneous presentation of multiple stimuli"), limited attention capacity, and the decision-making process.

A bout of EXTREME museum fatigue encapsulated a recent visit to the Vatican Museum (which left me feeling weird on many levels and could be a whole other essay…) but it also came down the fact that the combination of crowds, the pure amount of art/stimuli, being a part of a tour (my first time and last to do so and the only way that my friend and I could make the last-minute decision to go at all) and therefore a part of a timetable made by the tour guide (we were disciplined a few times when we heard in our headsets,“Where are the New Yorkers?!”, as we lingered a bit too long taking in some Arretine). Here I was, looking at some of humanity’s most impressive artistic achievements and failed to be struck, effected, or emotionally impacted at all. That could be the complicated feelings of being somewhere like Vatican City but it was also the many conditions that made it trick to simply pay attention in the first place.

To give or pay attention to a work of art—or anything for that matter—involves one’s eyes, mind, memory, and heart—powers of analysis, comparison, appreciation, and evaluation. Our attention doesn’t merely connect us to the world. It extends our sense of self into the world: It can be deep or broad, penetrating or subtle, acute or profound, specific or nuanced. When we don’t pay attention—when we don’t notice all the teeming things—it’s our selves failing to show up fully.

To see everything as art—whether it’s Raphael’s Academy, a steep cliff stretching out into the Balearic Sea, or your very own life—means to create the conditions to pay attention and to really notice. And often that’s simply giving yourself the time, space, freedom, and solitude to do so.

“Instructions for living a life:

Pay attention.

Be astonished.

Tell about it.”

- Mary Oliver

Thank you for this excellent rumination. And, thanks too for giving me a name for a sensation that I have been experiencing of late: museum fatigue. Coincidentally, it maxed out in the very same place - the Vatican Museum, in June of this year. The feeling carried through into our week at Rome, as a whole. So much to absorb from one city alone - history, architecture, art. It was overwhelming.

Beautiful piece.